5/17 – 5/18/19

Most weekends – summer and winter, rain or shine – I make time for some sort of outdoor activity. Whether hikes, bikes, or floats, these little excursions quicken a sedentary life, and give me an excuse to see some new corner of Chicago or the Midwest. Rewarding though they are for me, I generally assume that readers of this blog will not find them equally exhilarating, and never bother to write them up. This weekend’s trip to southernmost Illinois, however, was interesting enough to merit an exception.

Most of Illinois is notoriously flat and treeless. But the southern tip – hemmed in by Missouri on one side and Kentucky on the other – is hilly and forested, with rugged outcrops and rushing streams reminiscent of the Ozarks. Geographically and culturally, this part of the state is closer to Memphis than to Chicago: kudzu vines hang from cypresses and tupelos, and the local drawl is pure mid-southern. Southernmost Illinois is sometimes called Little Egypt. The nickname that may reflect its fertility, or perhaps its provision of food to the rest of Illinois during an early nineteenth-century famine. Whatever its origins, it captures the distinctive character of this thinly-populated and little-visited corner of the state.

I set out to explore Little Egypt on rainy Friday. Leaving around noon, I followed roughly 300 miles of ruler-straight roads past roughly 300 miles of newly-planted corn and bean fields. With the exception of the occasional bobbing oil jack, the scenery was uninspiring until the very end, when the Shawnee Hills reared on the southern horizon.

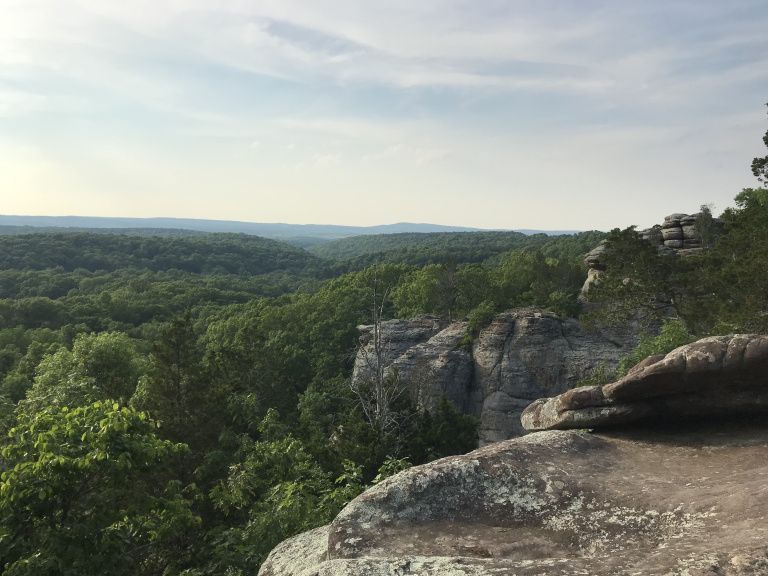

The Shawnee Hills are not especially lofty or picturesque, but they are hills; and in the Prairie State, that makes them something special. Their scenic highlight is the Garden of the Gods, a grandiosely-named series of sandstone knobs protruding from one of the Hills’ higher ridges. Although it was late afternoon by the time I arrived at the Garden, the weather was still hot and hazy, and relieved only by the slightest suggestion of a breeze. I had time only for a short walk between the most impressive rock formations, and returned to my car after a few pictures of wooded hills undulating off toward Kentucky.

A half-hour drive through dense woods brought me to Cave-in-Rock, a village on the banks of the Ohio River. Continuing to the adjacent and like-named State Park, I pitched my tent at the levelest site in a deserted campground. Then, as the sun set, I walked over to the cave after which the park and village were named, notorious in the late eighteenth century as a lair for outlaws preying on Ohio River traffic.

The cave was empty when I arrived. Walking inside, I clambered up to a ledge overlooking the Ohio, and turned to watch birds swooping and diving from the cliffs on either side to catch insects. A golden full moon, hazy in the humid air, hovered over the Kentucky bank. As darkness fell, I headed back through moon-drenched woods toward my campsite, where every insect in the Ohio valley waited hungrily for my return.

Saturday dawned sunny, windy, and warm. Breaking camp, I drove sixty miles west to the Lower Cache River, home of Illinois’ only cypress swamp. Though the bald cypress is a slow-growing species, it is capable of living for more than 2,000 years; and its wood is virtually imperishable. Appreciating these properties, nineteenth-century loggers destroyed most of the Mississippi Valley’s cypress swamps. The Cache river grove, however, managed to survive, and is now managed by the Illinois DNR, which has established a trail for paddlers. This – after dousing myself with bug repellent – I proceeded to paddle in my trusty inflatable kayak.

My first stop was Illinois’ largest cypress, a gnarled tree estimated to be 1200 years old. Although high water concealed the broadest part of the flared base, it was an impressive sight. I nearly got an uncomfortably close look when my kayak rode over a submerged knee and threatened to flip. I continued through avenues of cypresses to Eagle Pond, a half-acre pool lined by towering trees. The most impressive of these was a huge specimen surrounded (as a faded sign informed me) by no fewer than 209 knees, some more than ten feet tall.

After winding through more swamps and batting fruitlessly at mosquitoes in the sunny main channel, I returned to the launch, and set off southwest toward the narrow peninsula between the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. This corner of Illinois, flood prone but fertile, was among the most prosperous in the state during the nineteenth century. Since the Second World War, however, the population has fallen steadily; many towns have lost more than half their residents in the past thirty years alone. The village of Mounds, where I found virtually the entire business district abandoned, is sadly typical of the region.

Along the way south, I stopped in Mound City National Cemetery, established during the Civil War for soldiers who died in the nearby hospital. It was a quiet, windswept place, dominated by a colossal nineteenth-century monument for the veterans buried there. I walked up and down the main road, passing lines of headstones that seemed to quaver in the heat. Then, feeling time press, I returned to the car, and headed toward Cairo.

As I drove, I recalled my last visit to Cairo, three years before. Since its heyday a century ago, Cairo has lost nearly nine-tenths of its population, and virtually all of its wealth. Some grandiose old buildings remain, but sadly little else. The Mississippi and Ohio were in major flood stage, and many of the fields around the city lay beneath water deep enough to form whitecaps. Passing beneath a portcullis-like flood gate, I drove to the parking lot above Fort Defiance state park, beside the bridges leading to Kentucky and Missouri. After confirming that the park was underwater, I took my bike off its dusty rack and rode down to Cairo.

For an hour and a half, I pedaled up and down empty streets. The business district, which I had driven through three years ago, was still deserted; one collapsed building had been cleaned up, but the rear of another had dissolved into rubble. A few of the grandest houses, built for steamboat captains in the mid-nineteenth century, were well-maintained. A depressing number, however, had become kudzu-covered ruins.

The whole ride was reminiscent, sometimes uncomfortably so, of my cruises through Detroit – the fascination of decay, the bleakness of lost opportunity, the discomfort of feeling like a tourist to poverty. At least I managed to avoid running into any Detroit-style packs of feral dogs.

Returning to my car, I looked over the flooded Mississippi as I tried to decide my next move. I had planned to camp that night, and paddle another river the following morning. The forecast, however, called for thunderstorms; and my inflatable kayak was not really up to the challenge of negotiating swollen rivers or flood debris. So I headed home, stopping along the way to sample southern Illinois’ premier rib joint (good, but pricey). The rest was a quiet ride up I-57, past cornfields silvered by a hazy moon.